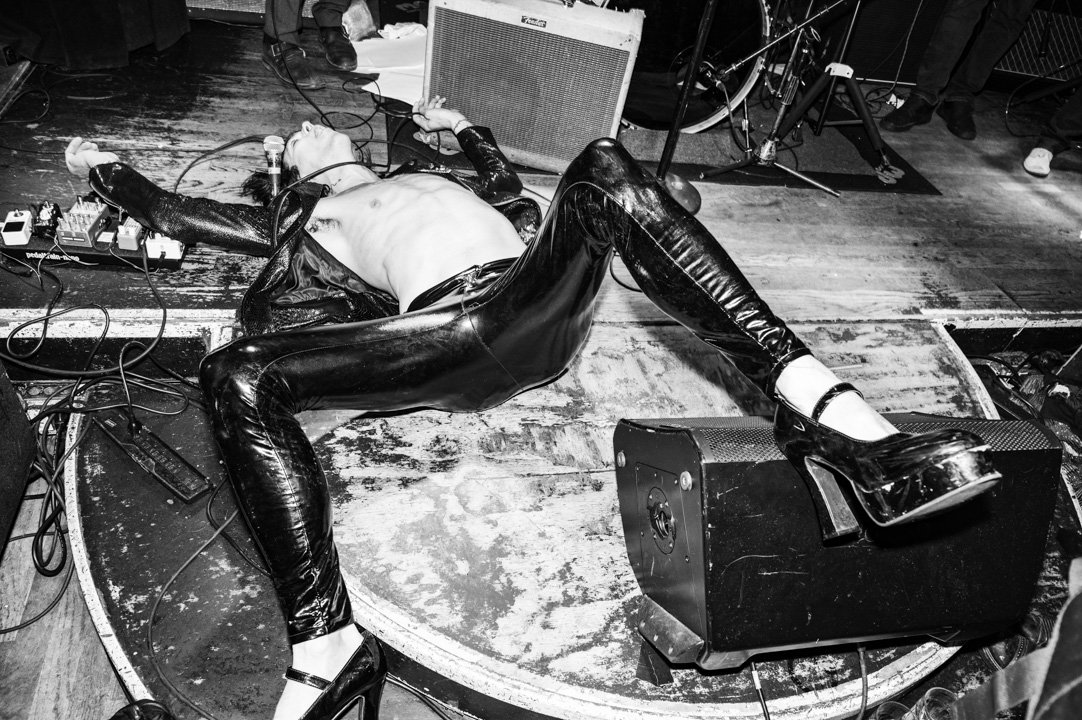

In the heart of the Lower East Side, Ki Smith Gallery celebrates fifty years of PUNK with an exhibition retracing the birth of the magazine and its role as both witness to and catalyst of a movement — the punk one — in the wild, incendiary New York of the ’70s and ’80s. The show brings together illustrations, photographs, and lithographs, and for the opening the gallery will also publish new issues of the magazine, in collaboration with photographer Nico Malvaldi, whose shots capture today’s New York underground

It’s hard to describe what New York – and in particular that area of the city known as Downtown – was during the wild and turbulent two decades of the ’70s and ’80s. Imagine for a moment a kind of Dantean inferno: burnt-out cars, homeless people, squatted buildings – a no man’s land where not even the police dared venture because everything was simply too frightening. Now place within this picture an artistic community at the absolute forefront of experimentation, one that took advantage of Downtown’s geographic and social isolation to create peculiar expressive forms aimed at breaking open the artistic medium itself. This community played a key role in the transition from modernism to postmodernism, which manifested primarily in artists’ desire to step outside the frame that defined the expressive space – and beyond the sanitized white cube of art galleries – to burst into the urban environment and the viewer’s intimacy, obliterating boundaries: the audience finally participated in the completion of the artwork. The frame – physically and metaphorically – was dismantled by postmodernist criticism; the content of the artwork was no longer self-referential but firmly connected to, and partly determined by, the outside world.

In the 1970s, Downtown’s art world was concentrated mostly in glossy SoHo, but only in the early ’80s did activity shift toward the East Village and the Lower East Side (LES). There, new galleries began to emerge with a more experimental spirit than their glamorous SoHo counterparts, and around the LES’s squatted buildings politically engaged artist collectives gathered, intent on pushing beyond what was considered the acceptable limit of visual arts and music. This is where avant-garde visual and musical movements like no wave were born – a nihilistic black wave that, drawing on the abrasive spirit of Dadaism and anarchism, proposed a transgressive, infected vision of the artistic medium. Wandering through Downtown’s dark corners – particularly the Village and the LES – meant risking an armed mugging, at the very least. I recently visited Julie Hair – a member of the iconic band 3 Teens Kill 4, which also included one of Downtown’s cult figures, David Wojnarowicz – who welcomed me into her home in Bushwick. I asked her what it was like living in the Village in the ’80s, and she told me, with astonishing calm, shrugging her shoulders, «Well, yeah, I was mugged once, someone held a knife to me, but nothing major».

In the 1970s, Downtown’s art world was concentrated mostly in glossy SoHo, but only in the early ’80s did activity shift toward the East Village and the Lower East Side (LES). There, new galleries began to emerge with a more experimental spirit than their glamorous SoHo counterparts, and around the LES’s squatted buildings politically engaged artist collectives gathered, intent on pushing beyond what was considered the acceptable limit of visual arts and music. This is where avant-garde visual and musical movements like no wave were born – a nihilistic black wave that, drawing on the abrasive spirit of Dadaism and anarchism, proposed a transgressive, infected vision of the artistic medium. Wandering through Downtown’s dark corners – particularly the Village and the LES – meant risking an armed mugging, at the very least. I recently visited Julie Hair – a member of the iconic band 3 Teens Kill 4, which also included one of Downtown’s cult figures, David Wojnarowicz – who welcomed me into her home in Bushwick. I asked her what it was like living in the Village in the ’80s, and she told me, with astonishing calm, shrugging her shoulders, «Well, yeah, I was mugged once, someone held a knife to me, but nothing major».

Filmmaker Vivienne Dick recalls with deep nostalgia her arrival in New York and especially her first steps in Downtown: everyone advised her not to go out alone at night, but she was mesmerized by the candy-colored neon of porn theaters, the soft lights of peep shows, and the dense, seedy atmosphere that seemed full of possibilities. Because every corner of Downtown was a possibility: this is where New York’s most famous sex clubs were born. This is where bands that would go on to write the history of international music took their first steps. This is where legendary venues like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City opened – the latter counting among its habitués figures such as Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Andy Warhol.

In 1973, the Mercer Arts Center – a historic Greenwich Village venue where New York Dolls, Suicide, and The Modern Lovers had performed, and where an embryonic punk rock scene was taking shape – collapsed. Not figuratively: it literally collapsed. At 5:10 p.m. on August 3, the building gave way, injuring several people and killing four.

It’s therefore reasonable to say that without the collapse of the Mercer Arts Center, CBGB (or more precisely, CBGB & OMFUG – Country, Bluegrass, Blues, and Other Music For Uplifting Gourmandizers) would likely have remained a dingy little bar on an even dingier Bowery – then one of Manhattan’s roughest arteries, populated by homeless people, addicts, and sex workers, and home to the unfortunate YMCA building later transformed by Burroughs into both residence and artist hangout. CBGB soon became an incubator of ideas and projects for young bands who could experiment there without the pressures of the mainstream music industry. Hilly Kristal agreed to take emerging musicians under his wing, among them the very young Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell (Television), soon followed by the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, and The Patti Smith Group, which significantly boosted the club’s fortunes. CBGB became synonymous with DIY, antagonism, hardcore matinées, punk, and new wave, but also with a return to a pure musical form, as Luca Frazzi explains in this interview given for the long-awaited Italian release of a CBGB classic, Roman Kozak’s This Ain’t No Disco: The Story of CBGB. Frazzi recounts that the club brought rock «back to the starting line»: though only twenty years old, rock had already grown old, far removed from the subversive, antagonistic spark that had set it in motion. CBGB reset everything, bringing rock back to the essentials – both musically and aesthetically – raw and unpolished, as also documented in Amos Poe’s film Blank Generation, which captured on film this crucial turning point in both American and international music history.

Documenting the birth and development of this fierce and vital counterculture was PUNK, the magazine founded in 1975 by John Holmstrom, Ged Dunn, and Legs McNeil and inspired by the caustic DIY aesthetic of underground comics blended with an ultra-vinyl pop sensibility. PUNK mixed illustrations, photographs, comics, and interviews with an unmistakably irreverent, sharp style, building its identity on the best DIY philosophy: as Holmstrom himself explained, anyone, regardless of technical skill or artistic talent, should have the opportunity to express themselves however they wish. With its peculiar visual language and journalistic focus on documenting the emerging New York punk rock scene, PUNK quickly became a reference point for the underground – a medium for disseminating the scene and a trendsetter in style.

In This Ain’t No Disco, Kozak recalls that it was PUNK that codified the movement’s look: a sea of black leather jackets, the compulsory outfit… the style was Debbie Harry’s – she wore a wedding dress on stage with the famous line, «This is the only dress my mother ever wanted me to wear». The magazine was instrumental in bringing together an embryonic punk scene whose contours were still rough and undefined. PUNK helped define and clarify the essential characteristics of this new musical scene, gathering them into a single term – punk – filled with meaning: the word itself was chosen for its shocking potential, «Punk was a dirty word at the time. Us putting Punk on the cover was like putting the word ‘fuck’ on the cover».

Arriving at CBGB for their first assignment – to interview the Ramones – Holmstrom, Legs McNeil, and Mary Harron discovered that Lou Reed was also at the club and managed to interview him. Reed, then fresh off Metal Machine Music, was already a major name in the music world, and by becoming the protagonist of PUNK’s first issue (January 1976), he gave the magazine the momentum it needed to establish itself as a new voice of New York’s underground. The UK import of PUNK #3 – featuring Joey Ramone on the cover – by Rough Trade also helped build hype around the band’s legendary 1976 show at the Roundhouse. True to its signature irony, PUNK became the mouthpiece for a counterculture focused on fundamental freedoms, anti-capitalism, and a rejection of mainstream conventions, using an expressive medium that aimed to convey authenticity through craft, raw aesthetics, collage, photocopies, and handwritten or typewritten text.

The pages of PUNK hosted not only artists like Iggy Pop, Debbie Harry, The Ramones, Brian Eno, David Byrne, and Joan Jett, but also offered space to new writers such as Mary Harron (director of American Psycho) and Anya Phillips – performer, designer, and key figure in several feminist no wave experimental films such as Vivienne Dick’s Guerrillere Talks – as well as photographers like Roberta Bayley and Godlis. The magazine’s brilliant run ended in 1979 after only 15 issues, followed by several special editions – the last published in 2007, for a total of 23 – but its influence in shaping punk’s aesthetic, protagonists, and philosophy was profound, inspiring later DIY publications and laying the tracks for the rich culture of punk fanzines.

To celebrate the birth of the punk movement and the history of the magazine, the Ki Smith Gallery in the Lower East Side, with the support of Ilegal Mezcal, has organized an exhibition presenting the best of 50 Years of PUNK! with drawings, illustrations, photographs, and lithographs. The show opens today, November 28, 2025 – exactly fifty years after the day PUNK interviewed the Ramones and Lou Reed – and will close on January 11, the date when the first copies of PUNK #1 were sold at CBGB. For the occasion, not only will issue #24 of PUNK be published – with illustrations by Johnny Moondog (Labretta Suede and Motel Six) – but also the exhibition catalog (PUNK #25), whose cover will be designed by none other than Shepard Fairey (OBEY). Moreover, for the first time in PUNK’s history, the magazine is opening up to a special collaboration with photographer Nico Malvaldi.

To celebrate the birth of the punk movement and the history of the magazine, the Ki Smith Gallery in the Lower East Side, with the support of Ilegal Mezcal, has organized an exhibition presenting the best of 50 Years of PUNK! with drawings, illustrations, photographs, and lithographs. The show opens today, November 28, 2025 – exactly fifty years after the day PUNK interviewed the Ramones and Lou Reed – and will close on January 11, the date when the first copies of PUNK #1 were sold at CBGB. For the occasion, not only will issue #24 of PUNK be published – with illustrations by Johnny Moondog (Labretta Suede and Motel Six) – but also the exhibition catalog (PUNK #25), whose cover will be designed by none other than Shepard Fairey (OBEY). Moreover, for the first time in PUNK’s history, the magazine is opening up to a special collaboration with photographer Nico Malvaldi.

Nico moved to the United States in the mid-’90s, and after a long career in fashion and sports photography, he entered New York’s underground scene in 2013, documenting it with passion and skill. Since the exhibition catalog will primarily focus on presenting the installation, Holmstrom decided to honor the magazine’s underground musical roots by entrusting the documentation of the more strictly musical component to someone who knows the stages well – Nico, one of the best live photographers on the New York scene and the most beloved by bands.

With a sophisticated and never banal eye and a sharp black-and-white style, Nico Malvaldi’s shots depict the underground river of energy that boils in a Ridgewood dive bar or a Lower East Side club – a river that ignites the lines of a skull tattooed on a musician’s head, reflects off the latex pants of a guitarist, and crashes in a thousand droplets of sweat from the stage onto the crowd pressed up against the speakers.

In 2016, Nico began printing his portfolio to disseminate his work and perspective on the scene, and over the years the publication – MANI – evolved into a full-fledged magazine with written contributions accompanying the photos taken in the studio or during live shows. It will therefore be MANI #30 (or PUNK 24 ½) that represents New York City’s contemporary underground within the publications dedicated to the fifty years of PUNK, inaugurating a series of four special issues in collaboration with Ki Smith Gallery and Ilegal Mezcal.

But this is only the beginning: soon, Nico and I will take you deep inside New York’s underground – in the middle of the mosh pit, in line at the bar, on the subway at night. Stay tuned, stay PUNK!